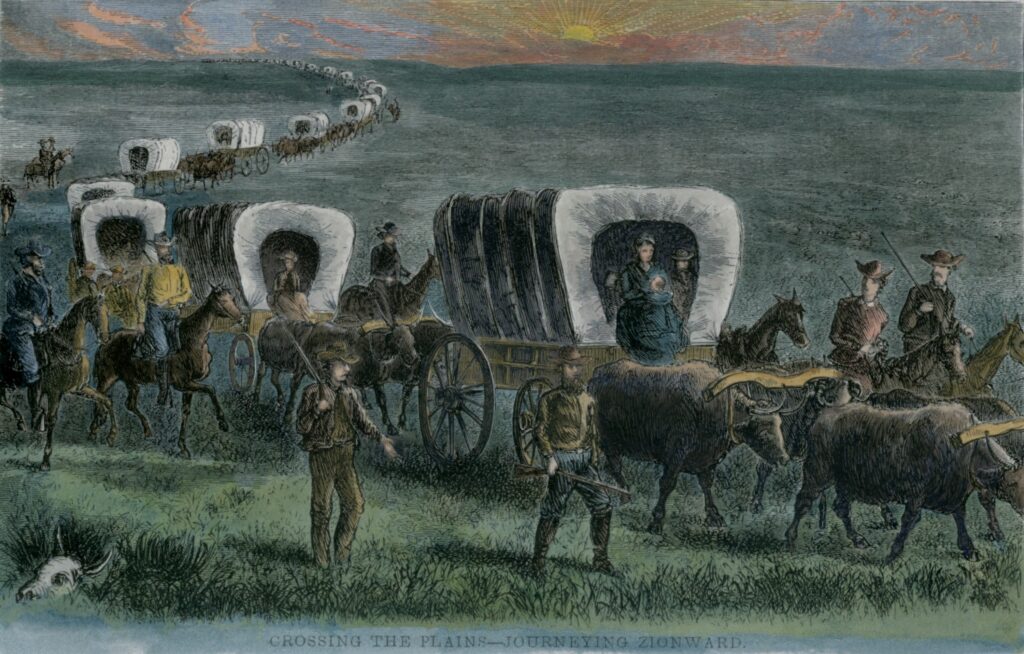

Crossing the Plains-Journey Zionward. The first of thousands of Mormon pioneers took a 1300-mile-long ‘Mormon Trail’ from Nauvoo.

By Everett Collection

On July 24, 1849, the Latter-Day Saints had been in the Salt Lake Valley two years to the day.

Just a few years earlier, their beloved prophet Joseph and patriarch Hyrum had been murdered and mobs had driven them from their homes along the banks of the Mississippi River. They sought redress from the government of the United States but to no avail. Their pleas fell on deaf ears as President Van Buren responded, “Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you.” Loading what little they had left into wagons and handcarts, they began the thousand-mile trek across the American West to settle in a remote region of the Great Basin.

On this day of celebration in 1849, they erected a flagpole 104 feet tall in the newly finished bowery on Temple Square. These same sisters who had been treated so mercilessly in Missouri and Illinois, spent weeks sewing an enormous American flag, 65 feet in length, which was now raised to the top of this “liberty” pole.

A brass band played as Brigham Young led a grand procession along Main Street to Temple Square, followed by the twelve apostles and the seventy. Then followed 24 young men dressed in white pants, black coats, white scarves on their right shoulders, coronets on their heads, and a sheathed sword at their sides. In their right hand each carried a copy of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. The Declaration was read by one of these young men.

Next came 24 young women dressed in red, white, and blue scarves on their right shoulders, and white roses in their hair. Each carried a Bible and a Book of Mormon.

It may seem surprising given the all too recent memory of their suffering, that for this first celebration in their new mountain home, our pioneer ancestors chose as their theme, patriotism and loyalty to that same government which had rejected them.

In the afternoon, Elder Phineas Richards gave this counsel, “We who have lived to three-score years have beheld the government of the United States in its glory, and in spite of our deprivations, the pure principles of our boasted Constitution remain unchanged. And as we have inherited the spirit of liberty and the fire of patriotism from our fathers, so let them descend to our posterity.”

Elder Richard’s comments were particularly poignant that day as his eldest son George had died at the tender age of 15…a victim of the Haun’s Mill Massacre of 1838.

Although outcast, these pioneers hoped to be reconciled and re-established in full faith and fellowship as citizens of their native country. They knew that citizenship is more than a matter of where you are born…that citizenship requires an active and engaging commitment. That unless one actively promotes the welfare of his community, he is an alien in the oldest sense of the term…“foreign to, or estranged from his fellow men.”

Given their experiences, it would have been easy to remain bitter, and cling to their grievances, yet these noble people chose a higher path. The common good and the principles of a free and democratic society were a greater priority to them than the personal injury they had sustained.

Fast forward 172 years. During the coming weeks, as we reflect upon the events of our pioneer past, what will be our role in the unfolding narrative of America? There is much to contemplate as our country struggles to respond to so many opposing voices, and to so many who no longer follow the path of civility in their public discourse. The unrest is growing, and it will fall to calmer voices to stem the tide.

Like our pioneer ancestors, are we strong enough to choose inclusion over exclusion, tolerance over intolerance, and forgiveness over retribution? Do our actions support the common welfare or are we mired in bitterness, keeping ourselves separate, angry, and withdrawn? We know that things won’t always go our way, and perhaps not often. We will be offended and justice won’t always be served. But, what is the more constructive approach to living in harmony with those who share our borders: grinding our axe to its bitter end, or using it to cut an olive branch? The legacy of July 24, 1849 is a wise answer.