Athalia Howe was just 12 years old when she, her sister and mother were forced to seek refuge in a cemetery as armed white supremacists terrorized Wilmington, North Carolina, in the fall of 1898. Separated from her father, they were unsure if he was still alive until days later when they reunited.

Decades after the incident, Howe had a flashback to that time. She grabbed the wrist of her great-granddaughter, Cynthia Brown, and screamed, “If it ever happens again, run! Don’t let it happen to you!”

“She had a very stark, distant look in her eyes,” Brown told ABC News, remembering the encounter. “I was very thrown. I didn’t know what to make of it. After that, no one talked about it, no one explained it.”

It would be years before she finally learned from family members what her great-grandmother was referencing: the Wilmington Coup of 1898, the only successful coup d’état in American history.

In this Nov. 6, 2021, file photo, community members gather at the Pine Forest Cemetery to honor Joshua Halsey who was killed in an attack attributed to a white supremacist mob in 1898, in Wilmington, North Carolina. Great Granddaughters of Halsey attended the service where Rev. Dr. William Barber, II eulogized Halsey.

Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images, FILE

Nearly 125 years later, the wounds of the deadly campaign still run deep in the city, with many residents saying Wilmington never made amends for the tragedy. Residents and activists continue to work towards uncovering that history and finding redress for the descendants of Black residents impacted by the violence.

The coup was spearheaded by Josephus Daniels, publisher of several influential newspapers in the state, and Furnifold Simmons, chairman of the state’s Democratic Party, to overthrow the elected biracial government in Wilmington, according to historians.

The plot, titled the “White Supremacy Campaign,” utilized propaganda, fiery speeches and intimidation by the Red Shirts, a militia group named for the red tunics they wore, to prevent Black and white Republican voters from turning out for the 1898 state and federal elections, historians say.

The plot succeeded and they effectively stole the election. But in Wilmington, several Black politicians still held office and the coup leaders did not want to wait until the following year to vote them out.

Men stand in front of The Daily Record, the only Black newspaper, after burning it to the ground

Courtesy of New Hanover County Public Library, North Carolina Room.

Two days later, on Nov. 10, 1898, a mob of nearly 2,000 white men torched the offices of Wilmington’s only Black newspaper, The Daily Record, and began indiscriminately shooting at Black residents across the city. At least 200 people were killed in the violence, although historians say the true number is hard to pinpoint. White leaders later spun the violence as a “race riot” that the militia needed to control.

In the following weeks, as many as 2,100 Black residents abandoned the city, historians say.

Amid the chaos, Alfred Waddell, a former confederate general and one of the leaders of the campaign, forced the resignation of several local officials and installed himself as mayor of Wilmington.

As a result of the violence, Jim Crow segregationist laws became entrenched in North Carolina and echoes of the event still manifest themselves over a century later. The Black population, once boasting the majority in Wilmington, now only makes up 17 percent of the city, according to the latest Census data from 2020.

What happened in Wilmington also became a model for other massacres like the one in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921.

“The violence in Wilmington became an example to other locations of how to have a riot and get away with killing people in the street based on race,” LeRae Umfleet, a lead researcher for a 2006 state report on the coup, told ABC News. “People from Atlanta spoke to people from Wilmington and asked them, ‘How did you do this, how were you able to neutralize the black vote? How was it that there was so many people killed, and no one was ever held accountable?'”

In this Nov. 8, 2019, file photo, people stand under the new North Carolina highway historical marker to the 1898 Wilmington Coup during a dedication ceremony in Wilmington, N.C. The marker stands outside the Wilmington Light Infantry building, the location where in 1898, white Democrats violently overthrew the fusion government of legitimately elected blacks and white Republicans in Wilmington.

Matt Born/The Star-News via AP, FILE

Brown grew up in Wilmington during segregation, but said she had a “romantic idea” of the community around her. As she learned about the history of the coup, that sentiment turned into anger and frustration.

“There was a generational robbery of values, of understanding one’s family tree, one’s family legacy. I realized there were people who had a snip if you will,” Brown said. “There was a disconnect for them because they had lost family history…family assets and family members.”

Brown said she recalls going to the public library after school with a friend to try and learn more about what happened. The library refused to show them any records even though they were stored there, Brown said.

She moved away for college, eager to leave the city behind, but returned to Wilmington after her mother suddenly passed away. It was then she says that she became more involved in community programs and working to preserve the history of the events of 1898.

Laura Ginther, a member of the New Hanover County Community Remembrance Project (NHCCRP), a group working to memorialize the victims of the massacre, calls Wilmington “a microcosm for every prejudice that can exist.”

“The students who go to the schools in the primarily Black areas of the town, their scores on education are worse. Their access to healthcare is worse, there’s no grocery store in the area,” she said.

The 2021 Cape Fear Inclusive Economy Report, a study that looks at the inclusivity of the economy in the Cape Fear region where Wilmington is located, found that 30 percent of Black residents fall below the federal poverty line compared to 11.9 percent of White residents. It also found that the median White household income is a little more than double that of the median Black income.

Kim Cook, a professor of sociology and criminology at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, and a restorative justice practitioner moved to the city in 2005 and said she was “distressed” by the “palpable” segregation. For a long time, she couldn’t understand the division until she learned about the events of 1898.

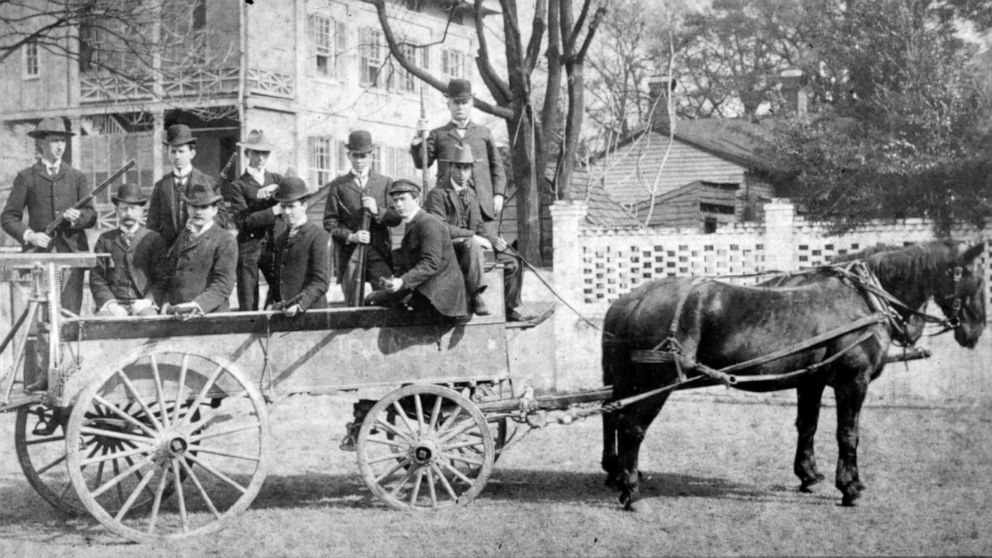

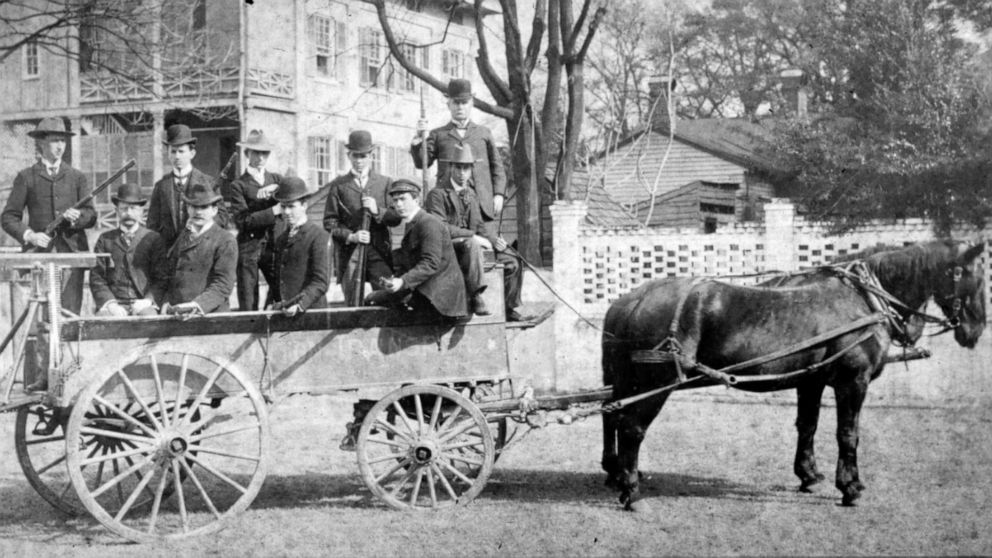

Men on a horse-drawn carriage on the day of the Wilmington Race Riot in 1898.

Courtesy of New Hanover County Public Library, North Carolina Room.

Now, she works with groups like NHCCRP and Coming to the Table, a national organization focused on healing the racial wounds of America’s past.

“The wound hasn’t healed,” she said. “I’ve been calling for a truth and reconciliation process in Wilmington for years that has fallen on deaf ears.”

As the 125th anniversary of the incident approaches, Wilmington residents are calling on the North Carolina legislature to hold true to the recommendations made in the 2006 report on the incident. The residents feel like nothing has been done beyond a grassroots level.

Some of the recommendations were put into legislative proposals, but most died in committee. The North Carolina Democratic Party issued an apology in 2007, acknowledging the party’s role in the coup and renouncing the past leaders.

Meanwhile, organizations like Third Person Project have worked to preserve and digitize copies of The Daily Record. The group also works in conjunction with the Equal Justice Initiative and other advocates to find descendants of victims and those who fled Wilmington using genealogical data.

Activists like Sonya Patrick are pushing for legislation to provide reparations for the descendants of those affected by the riot. She said change needs to be made to improve opportunities for Black residents of the city.

“When we don’t take action, and we don’t try to change things, that’s saying that we’re satisfied with the massacre, we’re satisfied with what happened,” Patrick said. “We should never be satisfied with that type of injustice.”