We’ve all been there: It’s a hot summer day, and you roll up to your local ice-cream shop for two scoops of double fudge chocolate chip. But alas — today, they’re all out, and all they have left is vanilla. You’re not exactly happy about it, but you order a scoop of it anyway, because, hey, some ice cream is better than no ice cream.

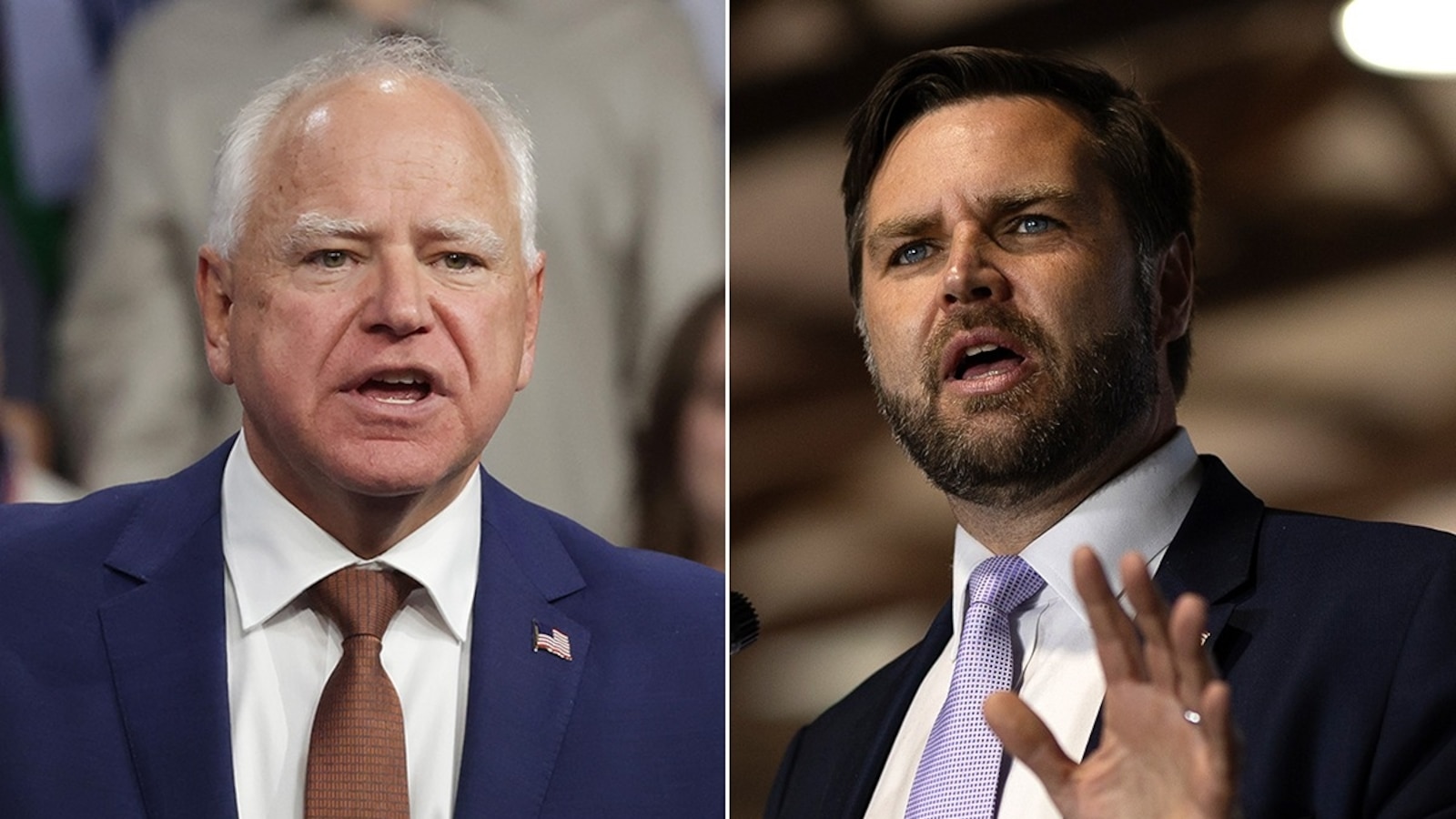

That’s basically the situation we’re in with debates. Barring a last-minute change of heart, former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris have debated for the last time this year, leaving only one major event on the campaign calendar: Tuesday’s vice presidential debate between Ohio Sen. JD Vance and Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz.

But the truth is, it’s just not the same. Typically, fewer people watch vice presidential debates than presidential debates. And while presidential debates are historically one of the few things that can actually make a dent in the polls, vice presidential debates don’t have the same track record. True, they can slightly impact how voters feel about the vice presidential nominees themselves — but at the end of the day, running mates don’t affect many people’s votes.

Vice presidential candidates tend to get overshadowed by their counterparts at the top of the ticket — and vice presidential debates usually do too. According to Nielsen, since 2008, presidential debates have drawn an average audience of 65.7 million people. But vice presidential debates have drawn an average of just 54.1 million viewers. In the last three presidential elections, the vice presidential debate was the least-watched debate of the fall.

But 54.1 million people is still a pretty big audience — so have past vice presidential debates actually changed the trajectory of the race? That turns out to be a tricky question to answer.

Normally, we’d check this by comparing what the polls said before the debate to what they said a couple of weeks later. If the polls shifted significantly in the wake of the debate, it would suggest (though not confirm!) that the debate made a difference.

But the problem is, most recent vice presidential debates have been followed very quickly by presidential debates. For instance, in 2000, there was a presidential debate six days after the vice presidential one. In 2008, 2012 and 2016, there was a presidential debate five days after the vice presidential one. And in 2004, there was a presidential debate just three days after the vice presidential one!

That doesn’t leave a lot of time for the (potential) impact of the vice presidential debate to show up in the polling before it’s (potentially) overwhelmed by the impact of the presidential debate. The chart below shows the 538 national polling averages* of the 2000-2020 presidential elections in the days immediately before and after the vice presidential debates. As you can see, they don’t move very much in the aftermath of vice presidential debates — and when they do move, it’s usually after the presidential debate has already occurred, making it likelier that the presidential debate caused the movement rather than the vice presidential debate.

The only time this century that the national polls moved more than 1 percentage point after the vice presidential debate but before the presidential debate was in 2000. In 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2016, the movement was negligible. Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean the vice presidential debate wouldn’t have affected the race — maybe the impact just didn’t have time to show up in the polls in the short window between the two debates. But in 2020, there was no presidential debate for more than two weeks after the vice presidential debate, and the polls barely budged during that time.

All of this isn’t to say that vice presidential debates have no impact whatsoever. It turns out that they can have small effects on the popularity of the vice presidential candidates themselves. We calculated polling averages of the favorable and unfavorable ratings of six recent non-incumbent vice presidential candidates around the time of their vice presidential debates.** Most of them saw some small change in their net favorability rating (favorable rating minus unfavorable rating) after the debate. Specifically, two weeks after the debate, their net favorability rating had shifted by an average of 2 points.

Going into Tuesday night’s debate, Walz is significantly more popular than Vance. As of Tuesday at 9 a.m. Eastern, Walz has an average net favorability rating of +4 points (40 percent favorable, 36 percent unfavorable). Vance, meanwhile, is underwater, with an average net favorability rating of -11 points (35 percent favorable, 46 percent unfavorable). Based on history, each candidate will have the opportunity to slightly change that at the debate. But it would also be a big surprise if the debate changes Americans’ overall feelings about the vice presidential nominees (i.e., if Vance suddenly becomes more popular than Walz).

And remember, vice presidential candidates themselves don’t matter all that much. Except in extraordinary circumstances, voters make up their minds based on the people who actually stand to wield power — the presidential candidates — not the ones who might potentially inherit it if something goes wrong. So even if the debate does change Americans’ perceptions of the vice presidential candidates, that likely won’t change their actual votes (as history has shown) — because few people are basing their votes on the vice presidential candidates to begin with.

G. Elliott Morris contributed research.

Footnotes

*Using our current polling-average methodology applied retroactively.

**Again, using our current favorability polling-average methodology applied retroactively. We had enough data to do this for all non-incumbent vice presidential candidates in the last 20 years except then-Sen. Joe Biden in 2008.