When the attorney representing former President Donald Trump before the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday had a chance to offer a rebuttal to government prosecutor Michael Dreeben, John Sauer took a pass.

“Nothing further, your honor,” he said.

The forfeiture of five minutes of uninterrupted time to drive home Trump’s claim of “absolute immunity” from criminal prosecution related to official acts while in the White House was a telling indicator of how his legal team feels it fared.

A majority of justices during the nearly three hours of historic arguments clearly didn’t buy the full sweep of Trump’s assertion of executive power — but in the end, that may not matter much.

Even before the gavel dropped in Trump v. United States, Sauer had effectively surrendered that unprecedented claim, conceding first that a former president could, in fact, be prosecuted for an official act if he had already been impeached and convicted by the Senate for it.

And later, Sauer granted that personal or private conduct — unrelated to the office but committed while in office — could also be fair game.

“You concede that private acts don’t get immunity?” Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked at one point.

“We do,” Sauer replied.

What was left was a contentious debate over what types official acts by a president are protected from judicial and prosecutorial review, which are not and how to make that determination.

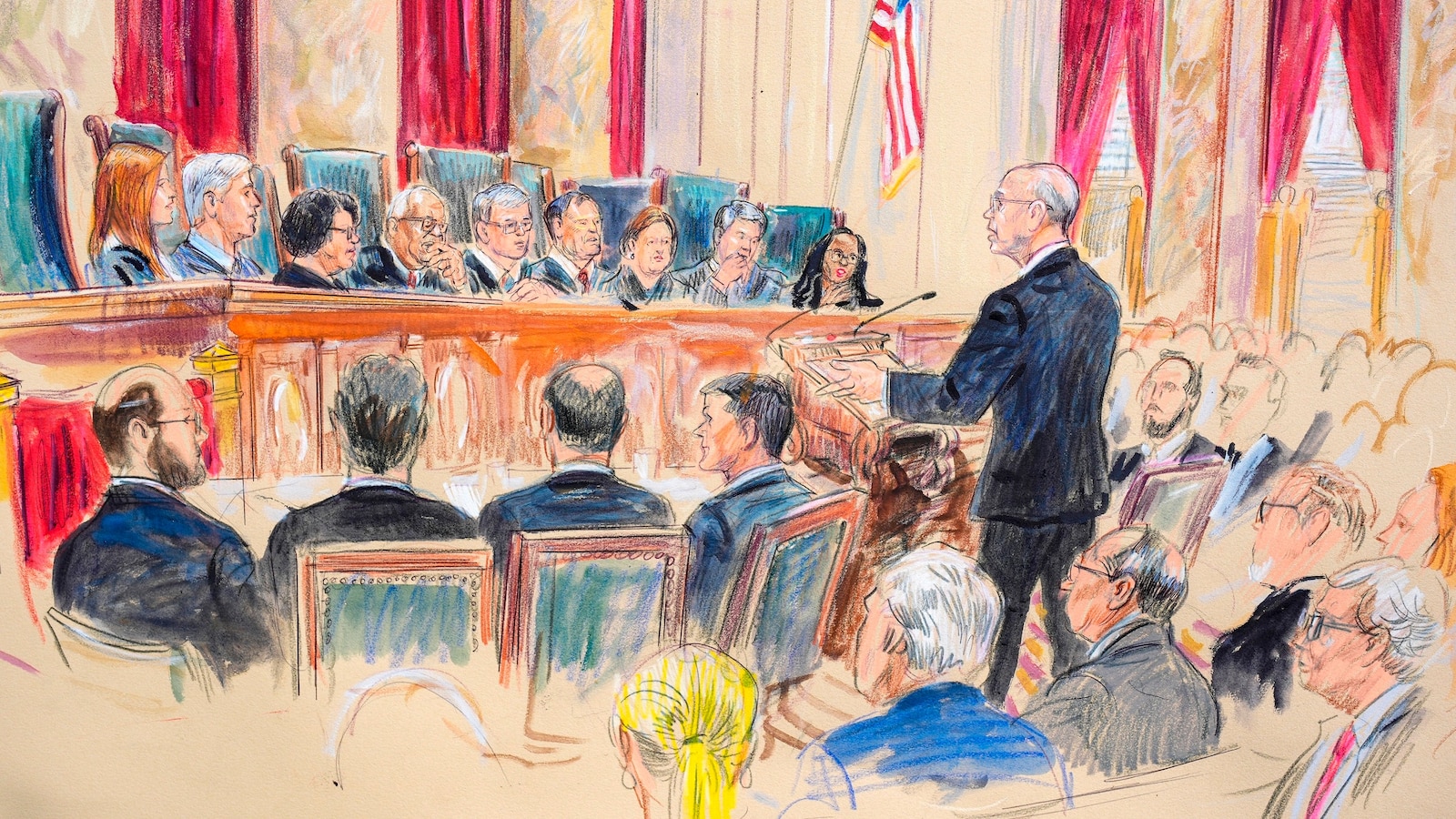

The artist sketch depicts former President Donald Trump’s attorney John Sauer speaking before the Supreme Court in Washington, Apr. 25, 2024.

Dana Verkouteren/AP

Much of the time saw the members of the high court posing various — sometimes provocative — hypotheticals about how a president could act under whatever the new guidelines of criminal liability will be.

Could he stage a coup? Assassinate a rival? And, assuming there was no immunity, could a past commander in chief have been prosecuted, like Franklin D. Roosevelt for certain controversial actions taken during World War II? Could a future leader be hounded by the specter of bad faith charges?

“We’re writing a rule for the ages,” Justice Neil Gorsuch said.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh agreed: “This case has huge implications for the presidency, for the future of the presidency, for the future of the country.”

Most of the court’s conservatives appeared ready to toss out an appeals court’s categorical rejection of immunity for Trump, which would have immediately cleared the way for his federal election subversion trial on four felony counts of conspiracy, obstruction and civil rights violation pertaining to the 2020 election and his push to remain in office. He denies all wrongdoing.

“What concerns me is … the court of appeals did not get into a focused consideration of what acts we’re talking about or what documents we’re talking about,” said Chief Justice John Roberts.

The resulting decision from the court will likely mean a narrowing of the Jan. 6 case against Trump based on whatever rule the majority devises for what official acts are fair game for prosecution.

This artist sketch depicts, from left, Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, Associate Justice Elena Kagan, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson during arguments in Washington, Thursday, April 25, 2024.

Dana Verkouteren/AP

“How do we define what an official act is?” Justice Clarence Thomas wondered at one point.

“Do we look at motives, the president’s motives for his actions?” mused Gorsuch.

Justice Samuel Alito posited: “If the president gets advice from the attorney general that something is lawful, is that an absolute defense?”

But Justice Sonia Sotomayor, among the liberals, noted that “there are some things that are so fundamentally evil that they have to be protected against.” She offered one of the most notable hypotheticals, about a president using the military to target a corrupt rival, which Trump’s attorney contended could “well be” protected as official conduct.

How soon will a landmark decision articulating the boundaries of presidential immunity and presidential power come down? There was no indication on Thursday it would be quick; instead, the historical gravity of the pending opinion suggested the justices would take their time in drafting it — possibly well into June, in the twilight of their term.

For Trump, whose political ambitions and legal strategy have leaned heavily on delay tactics in court, the ticking clock offers a huge advantage.

Whatever decision comes down, a lower court will need more time to sort out how it applies.

“The normal process,” Justice Barrett pointed out, “would be for us to remand [to a lower court] if we decided that there were some official acts immunity and to let that be sorted out below.”

This artist sketch depicts Michael Dreeben, counselor to Special Counsel Jack Smith as he argues before the Supreme Court in Washington, Apr. 25, 2024.

Dana Verkouteren/AP

It appears less likely than ever that a federal trial for Trump over his effort to overturn the results of the 2020 election will commence — much less be decided — before voters head to the polls in November to choose, again, between him and President Joe Biden.

But for those looking to see Trump held accountable in court, that opportunity may not be entirely lost.

In one notable exchange, Barrett methodically pressed for clarity from Sauer, Trump’s attorney, on whether certain allegations in his indictment were private conduct, which would not be shielded by immunity. Sauer said Trump continues to dispute the case but acknowledged the alleged acts all appeared personal, not official.

That point arose again, later in the arguments.

“Even if we decide here something — a rule that’s not the rule that you prefer… there’s sufficient allegations in the indictment in the government’s view that fall into the private acts bucket that the case should be allowed to proceed?” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked Dreeben, representing special counsel Jack Smith.

“Correct,” he replied.

“In an ordinary case, it wouldn’t be stopped just because some of the acts are allegedly immunized … if there are other acts that aren’t, the case would go forward?” Jackson continued.

He answered: “That is right.”