LOUISVILLE, Ky. — On his first day of school at Newcomer Academy, Maikel Tejeda was whisked to the school library. The 7th grader didn’t know why.

He soon got the point: He was being given make-up vaccinations. Five of them.

“I don’t have a problem with that,” said the 12-year-old, who moved from Cuba early this year.

Across the library, a group of city, state and federal officials gathered to celebrate the school clinic, and the city. With U.S. childhood vaccination rates below their goals, Louisville and the state were being praised as success stories: Kentucky’s vaccination rate for kindergarteners rose 2 percentage points in the 2022-2023 school year compared with the year before. The rate for Jefferson County — which is Louisville — was up 4 percentage points.

“Progress is success,” said Dr. Mandy Cohen, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But that progress didn’t last. Kentucky’s school entry vaccination rate slipped last year. Jefferson County’s rate slid, too. And the rates for both the county and state remain well below the target thresholds.

It raises the question: If this is what success looks like, what does it say about the nation’s ability to stop imported infections from turning into community outbreaks?

Local officials believe they can get to herd immunity thresholds, but they acknowledge challenges that includes tight funding, misinformation and well-intended bureaucratic rules that can discourage doctors from giving kids shots.

“We’re closing the gap,” said Eva Stone, who has managed the county school system’s health services since 2018. “We’re not closing the gap very quickly.”

Public health experts focus on vaccination rates for kindergartners because schools can be cauldrons for germs and the launching pad for community outbreaks.

For years, those rates were high, thanks largely to mandates that required key vaccinations as a condition of school attendance.

But they have slid in recent years. When COVID-19 started hitting the U.S. hard in 2020, schools were closed, visits to pediatricians declined and vaccination record-keeping fell off. Meanwhile, more parents questioned routine childhood vaccinations that they used to automatically accept, an effect that experts attribute to misinformation and the political schism that emerged around COVID-19 vaccines.

A Gallup survey released last month found that 40% of Americans said it is extremely important for parents to have their children vaccinated, down from 58% in 2019. Meanwhile, a recent University of Pennsylvania survey of 1,500 people found that about 1 in 4 U.S. adults think the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine causes autism — despite no medical evidence for it.

All that has led more parents to seek exemptions to school entry vaccinations. The CDC has not yet reported national data for the 2023-2024 school year, but the proportion of U.S. kindergartners exempted from school vaccination requirements the year before hit a record 3%.

Overall, 93% of kindergartners got their required shots for the 2022-2023 school year. The rate was 95% in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Officials worry slipping vaccination rates will lead to disease outbreaks.

The roughly 250 U.S. measles cases reported so far this year are the most since 2019, and Oregon is seeing its largest outbreak in more than 30 years.

Kentucky has been experiencing its worst outbreak of whooping cough — another vaccine-preventable disease — since 2017. Nationally, nearly 14,000 cases have been reported this year, the most since 2019.

The whooping cough surge is a warning sign but also an opportunity, said Kim Tolley, a California-based historian who wrote a book last year on the vaccination of American schoolchildren. She called for a public relations campaign to “get everybody behind” improving immunizations.

Much of the discussion about raising vaccination rates centers on campaigns designed to educate parents about the importance of vaccinating children — especially those on the fence about getting shots for their kids.

But experts are still hashing out what kind of messaging work best: Is it better, for example, to say “vaccinate” or “immunize”?

A lot of the messaging is influenced by feedback from small focus groups. One takeaway is some people have less trust in health officials and even their own doctors than they once did. Another is that they strongly trust their own feelings about vaccines and what they’ve seen in Internet searches or heard from other sources.

“Their overconfidence is hard to shake. It’s hard to poke holes in it,” said Mike Perry, who ran focus groups on behalf of a group called the Public Health Communications Collaborative.

But many people seem more trusting of older vaccines. And they do seem to be at least curious about information they didn’t know, including the history of research behind vaccines and the dangers of the diseases they were created to fight, he said.

Some of the CDC’s recent communications take a gentle approach.

One example is a digital media ad that depicts a boy playing with a toy Tyrannosaurus rex. The caption reads, “He thinks ‘diphtheria’ is the name of a dinosaur.” It’s an attempt to use humor while sending a message that children no longer know much about the infections that used to be common threats — and it’s better to keep it that way.

Dolores Albarracin has studied vaccination improvement strategies in 17 countries, and repeatedly found that the most effective strategy is to make it easier for kids to get vaccinated.

“In practice, most people are not vaccinating simply because they don’t have money to take the bus” or have other troubles getting to appointments, said Albarracin, director of the communication science division within Penn’s Annenberg Public Policy Center.

That’s a problem in Louisville, where officials say few doctors were providing vaccinations to children enrolled in Medicaid and fewer still were providing shots to kids without any health insurance. An analysis a few years ago indicated 1 in 5 children — about 20,000 kids — were not current on their vaccinations, and most of them were poor, said Stone, the county school health manager.

A 30-year-old federal program called Vaccines for Children pays for vaccinations for children who Medicaid-eligible or lack the insurance to cover it.

But in a meeting with the CDC director last month, Louisville health officials lamented that most local doctors don’t participate in the program because of paperwork and other administrative headaches. And it can be tough for patients to get the time and transportation to get to those few dozen Louisville providers who do take part.

The school system has tried to fill the gap. In 2019, it applied to become a VFC provider, and gradually established vaccine clinics.

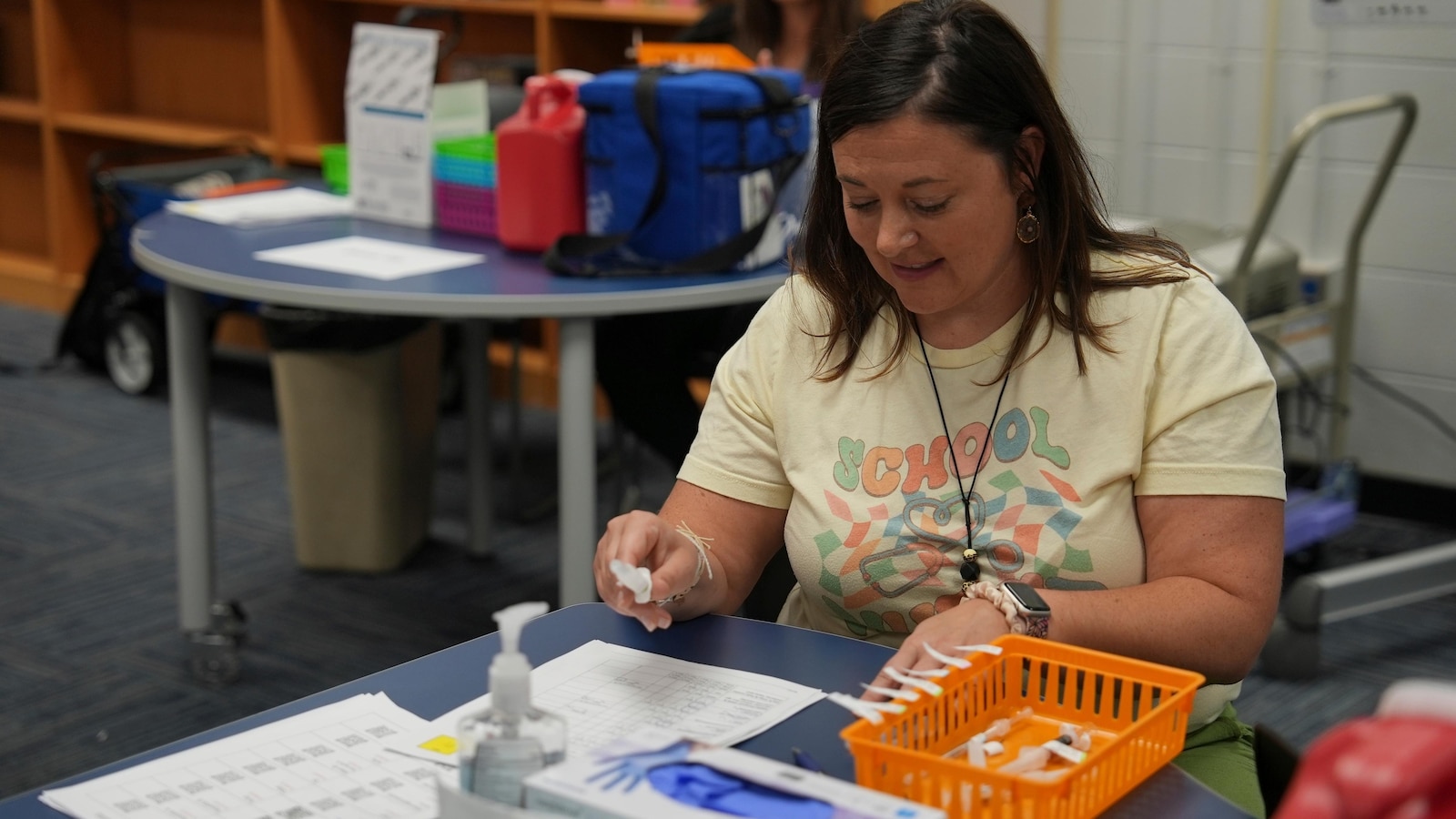

Last year, it held clinics at nearly all 160 schools, and it’s doing the same thing this year. The first was at Newcomer Academy, where many immigrant students behind on their vaccinations are started in the school system.

It’s been challenging, Stone said. Funding is very limited. There are bureaucratic obstacles, and a growing influx of children from other countries who need shots. It takes multiple trips to a doctor or clinic to complete some vaccine series. And then there’s the opposition — vaccination clinic announcements tend to draw hateful social media comments.

But there’s also a lot of support. The local health department and nursing schools are crucial partners, and city leaders support the endeavor.

At the recent vaccination celebration, Mayor Craig Greenberg acknowledged access problems and that vaccinations have become politicized.

But “to me, there’s nothing political about improving public health, about improving the health of our kids,” said Greenberg, a Democrat. “There should be no debate about that.”

___

AP video journalist Mary Conlon contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.