Army attack helicopter pilot Larry Taylor scrambled to rescue a small patrol of soldiers surrounded by enemies on the ground in Vietnam, according to a dramatic account he and the men he helped save tell about the life-and-death moments more than five decades ago.

Flying them out seemed to be the only option, but there was a problem: his Cobra gunship had no room inside. With bold action and quick thinking, he found a way to get them out of danger.

More than 55 years later, Taylor’s heroism will be recognized by President Joe Biden when he is awarded the Medal of Honor on Sept. 5, an upgrade from the Silver Star he originally received, the White House announced Friday.

On the night of June 18, 1968, a four-man long-range reconnaissance team saw through its night-vision scope that it was completely surrounded by hostile forces on a mission northeast of Saigon. It seemed inevitable they would soon be discovered and overrun, David Hill, a member of the team, recalled during a roundtable with reporters Monday.

When Hill’s team leader, Bob Elsner, radioed for support, Taylor, his co-pilot, and another Cobra crew were put into action.

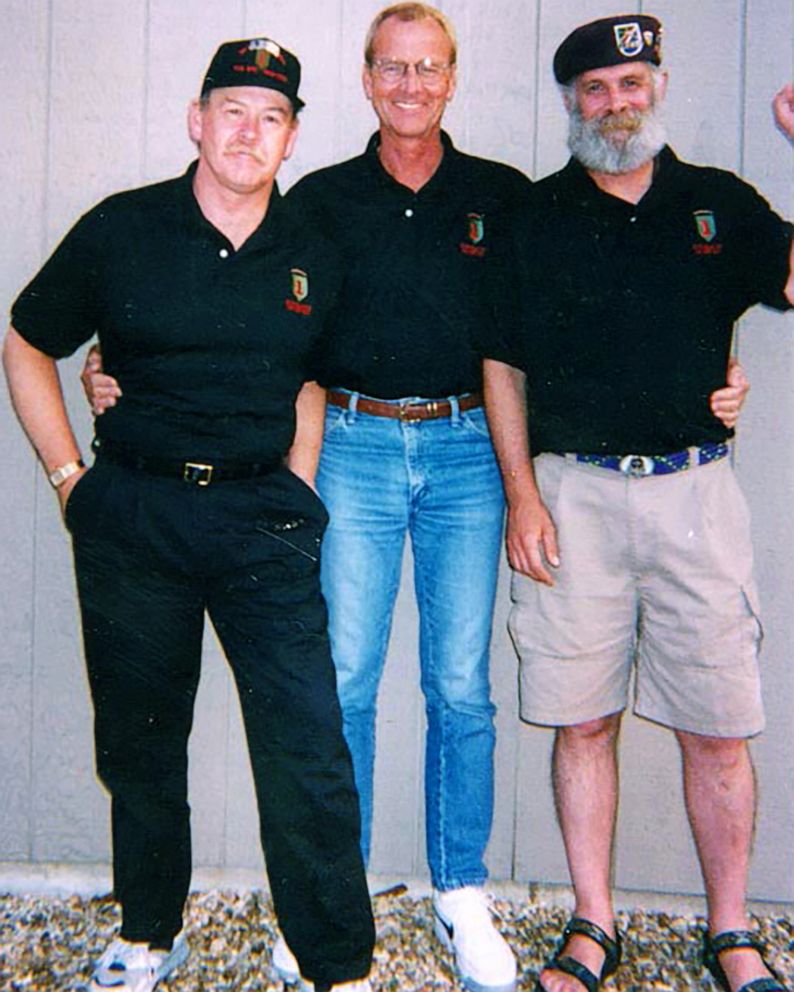

Photo of (L-R) Dave Hill, Larry Taylor, and Paul Elsner taken in 1999 in Branson, Missouri, at an annual 1st Inf. Div. LRP-Ranger Reunion. It was the first time Hill and Elsner met Taylor since he rescued them in Vietnam on the night of 18 June 1968.

Courtesy of Dave Hill

“Larry Taylor and his team had two minutes maximum to get off, strap in, turn the ship on, crank it up and get in the air and head in our direction,” Hill said.

Arriving above the patrol area, Taylor couldn’t see the team through the darkness. To avoid friendly fire, he radioed to the ground team leader to signal their location with a flare, though they knew this would also mean giving away their position to the enemy.

“He said ‘go,’ we popped the flares, and all hell broke loose,” Hill said.

Taylor and his wingman began strafing the surrounding enemies with rockets and mini-gun fire, keeping up their attack runs for 35 minutes.

But as the helicopters ran low on ammunition and fuel, the attackers continued closing in, firing small arms and rocket-propelled grenades at the team. Taylor learned that a rescue plan involving a UH-1 Huey helicopter had been cancelled “because it stood almost no chance of success,” according to the Army.

No other help was coming.

“Taylor decided on a bold and innovative plan to extract the team using his two-man Cobra helicopter, a feat that had never been accomplished or even attempted,” the Army release said.

He and the other Cobra pilot fired their remaining rounds along the team’s flanks. Taylor then switched on his gunship’s landing lights to distract the hostiles as the team moved to an area he had designated 100 meters away.

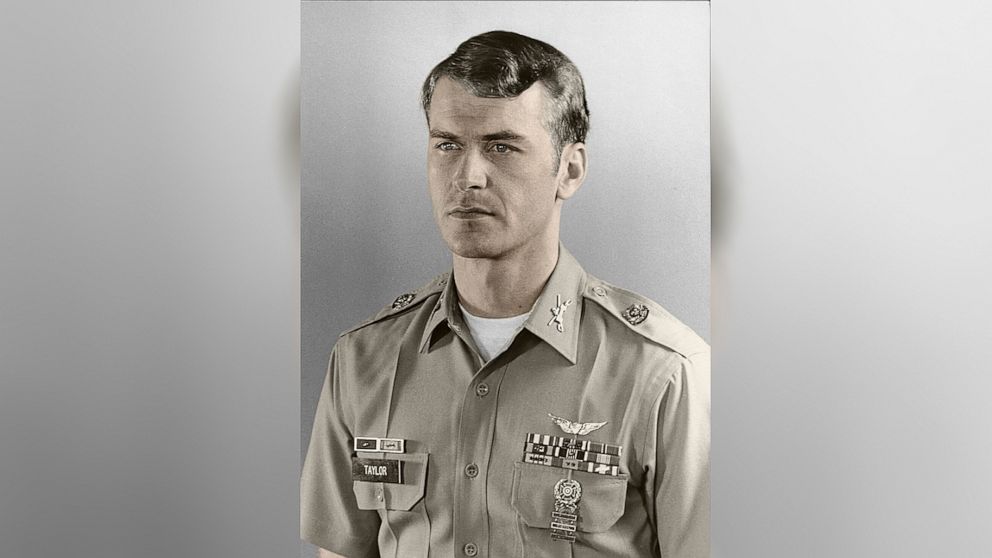

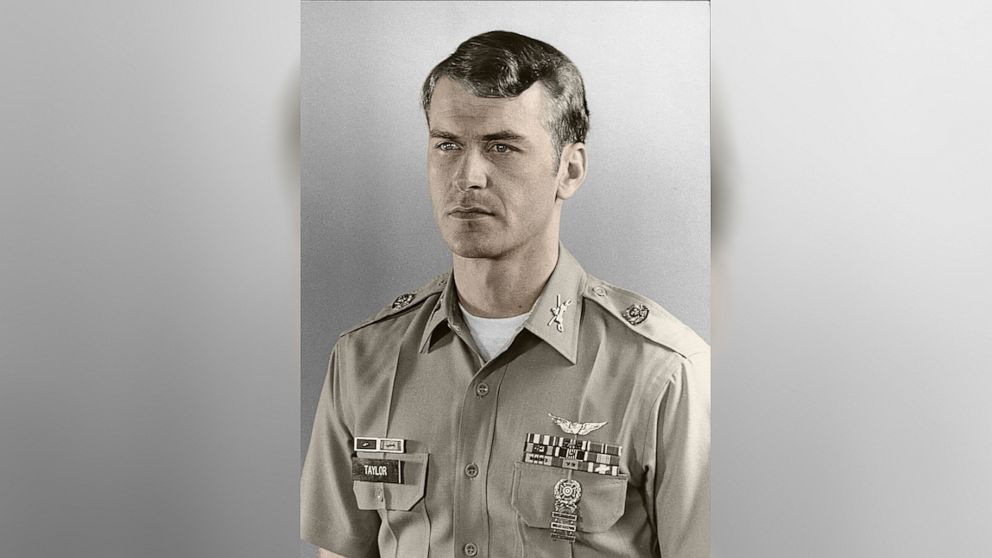

Service photo of Capt. Larry Taylor.

U.S. Army

“We were able to make a breakout finally because he had directed us through the very weakest portion of the enemy envelopment,” Hill said.

The team was also out of ammunition, except for a dozen hand grenades. While moving, Hill lobbed them behind and to the sides of the team to keep adversaries at bay until they reached the site.

“I knew that if I didn’t go down and get ’em, they wouldn’t make it,” said Taylor, who also spoke to reporters on Monday.

“We feel this big down rush of Larry’s … rotor, and he lands beside us,” Hill said.

Elsner passed on a radio message from Taylor to his team: “I’m on the ground for no more than 10 seconds — you and your folks find a place on my ship and I’m gonna get us all out of here,” Hill recalled.

The team members clung to the skids and rocket pods of the helicopter. “And that was our seat for the night,” Hill said.

“They beat on the side of the ship twice, which meant, ‘haul ass,’ and we did,” Taylor said.

Despite flying out of small arms range, the team was not yet out of danger.

“They’re wet. You put them on the outside of a ship and fly it at 150 miles an hour and they’d turn into icicles; they’d cramp up and let go and fall off,” Taylor said.

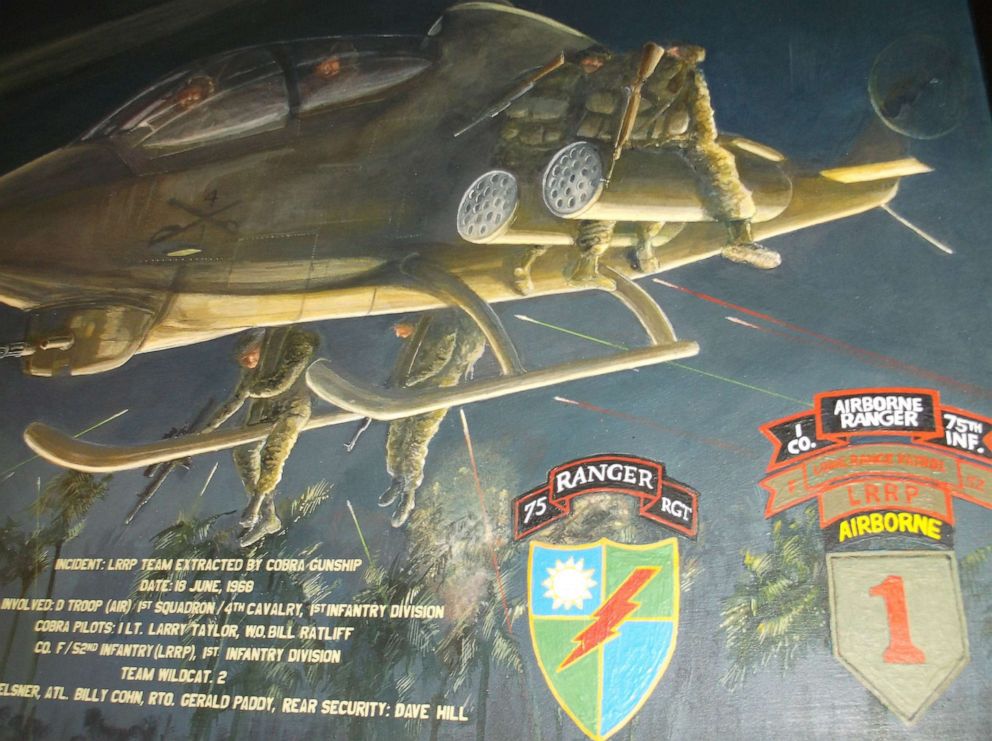

A painting by Darren Hostetter shows Larry Taylor picking up the reconnaissance team.

U.S. Army

Taylor decided to bring them to the nearest viable spot, dropping them off at a water treatment plant occupied by American forces.

“The four of them ran out in front of the helicopter, and then they turned around and lined up, and all four of them saluted,” Taylor said.

For his actions that night, Taylor received the nation’s third highest decoration for valor, an award Biden will be upgrading at a Medal of Honor ceremony scheduled for September 5 at the White House.

ABC News asked Hill what his team’s chance of survival was had it not been for Taylor.

“Absolutely zero,” he said. “We had only our Ka-Bar knives for defense.”

But Hill never met his rescuer face to face until more than 30 years later, when he, Elsner and Taylor attended a 1999 1st Infantry Division Long Range Patrol-Ranger reunion in Branson, Missouri.

“That was the first time I could actually meet him and thank him for his bravery,” Hill said. “We’ve been friends ever since.”