Nearly two decades after the launch of the first HPV vaccine, mounting evidence shows that people who got vaccinated are dramatically less likely to develop HPV-related cancers in adulthood.

HPV is a common viral infection that causes an estimated 690,000 cases of cancer every year across the globe, according to researchers from the World Health Organization. The virus infects specific tissues, predisposing patients to develop cancers – including cervical, anal, and head and neck cancer.

First approved in 2006, the HPV vaccine was initially marketed to young women as prevention for cervical cancer. It has since been updated to protect against additional HPV strains and is now recommended for boys as well, to reduce the risk of anal and head and neck cancers. The vaccine is currently recommended for children aged 11 or 12, unvaccinated adults until age 26 and can be recommended by clinicians up to age 45.

Now, experts are seeing early signs of the benefits of cancer prevention.

In early 2024, Scotland found zero cases of cervical cancer for patients who were vaccinated at age 12 or 13. The report was one of the first population-level studies looking at hundreds of thousands of patients vaccinated for HPV through a routine vaccination program for children with a high uptake of 80%.

The benefits extend beyond cervical cancer. For high-income countries like the United States, the incidence of head and neck cancer has since surpassed cervical cancer as the main HPV-related cancer.

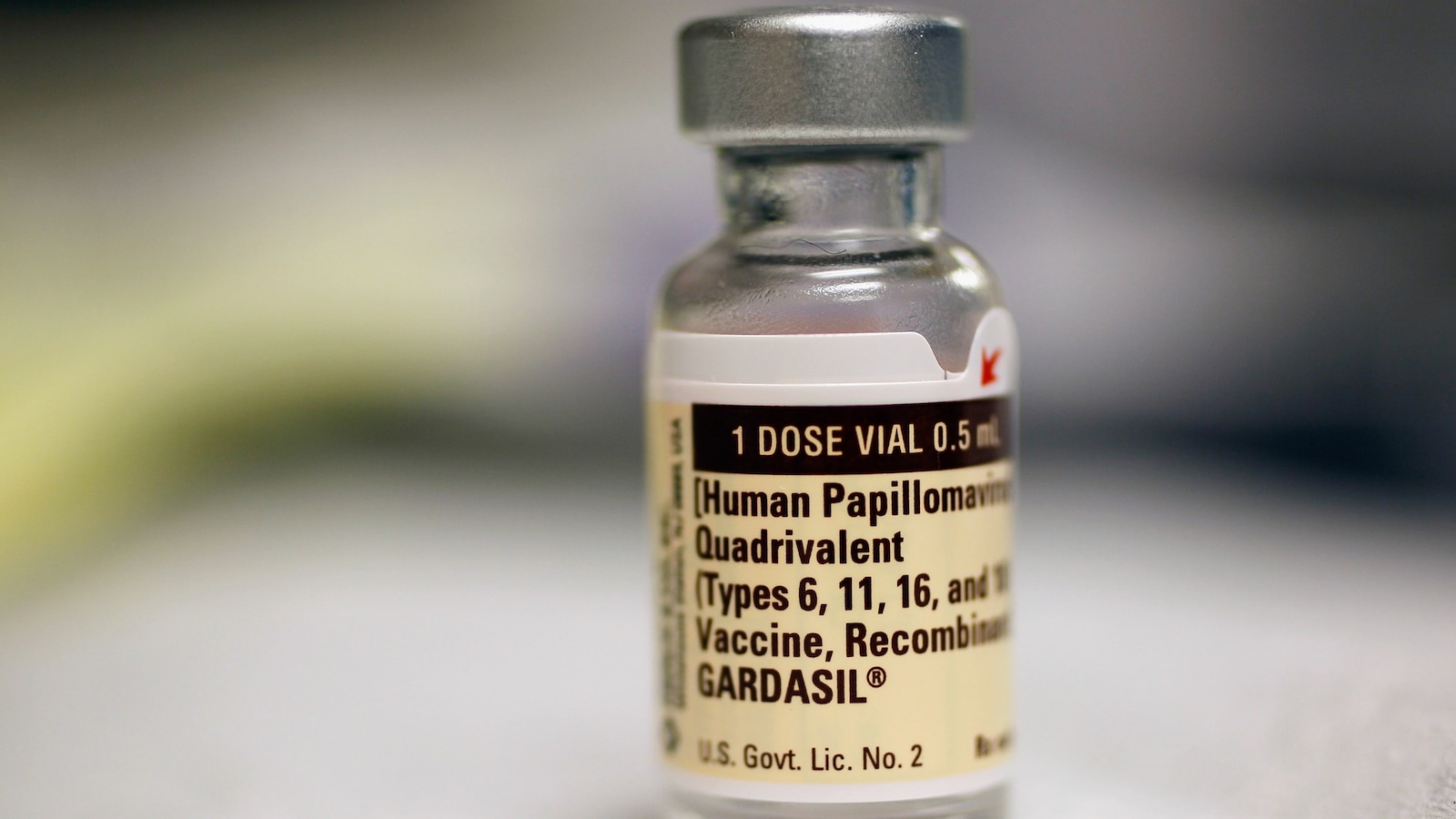

A bottle of the Human Papillomavirus vaccination is seen at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Miami, FL, Sep. 21, 2011.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

In May, at the 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) conference, preliminary reports showed a 56% reduction in the risk of developing HPV-associated head and neck cancer in vaccinated men.

“The ASCO study results are exciting in that it begins to suggest what we all have long expected, which is that HPV-vaccination will have a marked impact on reducing the incidence of HPV-associated head and neck cancer,” said Dr. Michelle Chen, a head and neck cancer surgeon and Assistant Professor at Stanford University who has studied HPV vaccination rates.

Based on data, it’s likely that the full benefits of the HPV vaccine will be realized in decades to come, said Dr. Erich Sturgis, a professor at the Baylor Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery who works as a surgical oncologist and epidemiologist focusing on HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers.

“It’s probably going to be a couple more decades before we really see the impact because overwhelmingly it’s those in their 50s, 60s and 70s who are getting these cancers,” said Sturgis.

Doctors said another encouraging sign is that people are signing up to get vaccinated. “These vaccines are safe, effective, and long-lasting,” Sturgis said.

A preliminary study from the 2024 ASCO conference showed that uptake of the HPV vaccine in the United States has gradually improved from 23.3% in 2011 to 43% in 2020.

“Overall, we are generally headed in the right direction with increasing rates of HPV vaccination, especially among males who have always lagged behind females,” said Chen.

However, doctors are still pushing every eligible person to get vaccinated. The percent of teens up-to-date on their HPV vaccination stagnated around 63% as of 2022 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“As a whole, we are far behind the Healthy People 2030 goal of 80% rate of HPV vaccination,” Chen said.

Adolescent boys are a key group that continue to lag behind, she told ABC News. Opportunities to close the gap include “targeted community vaccination campaigns, offering the HPV vaccination at the time of the flu shot, and elimination of any cost barriers.”

There are several barriers to pre-teens receiving the HPV vaccine. According to doctors, many parents are unaware of the benefits or cite safety concerns. Other parents feel like the vaccine is inappropriate for their children based on perceptions or beliefs about sexual activity.

“We have an incredible opportunity to prevent cancer in the next generation by the simple process of getting two vaccines in childhood,” Sturgis said. “To miss out on this opportunity is a real tragedy.”

Arifeen Rahman, MD is a resident in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.