LONDON — The host of a news conference about WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s extradition fight wryly welcomed journalists last week to the “millionth” press briefing on his court case.

Deborah Bonetti, director of the Foreign Press Association, was only half joking. Assange’s legal saga has dragged on for well over a decade but it could come to an end in the U.K. as soon as Monday.

Assange faces a hearing in London’s High Court that could end with him being sent to the U.S. to face espionage charges, or provide him another chance to appeal his extradition.

The outcome will depend on how much weight judges give to reassurances U.S. officials have provided that Assange’s rights won’t be trampled if he goes on trial.

Here’s a look at the case:

Assange, 52, an Australian computer expert, has been indicted in the U.S. on 18 charges over Wikileaks’ publication of hundreds of thousands of classified documents in 2010.

Prosecutors say he conspired with U.S. army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning to hack into a Pentagon computer and release secret diplomatic cables and military files on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

He faces 17 counts of espionage and one charge of computer misuse. If convicted, his lawyers say he could receive a prison term of up to 175 years, though American authorities have said any sentence is likely to be much lower.

Assange and his supporters argue he acted as a journalist to expose U.S. military wrongdoing and is protected under press freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Among the files published by WikiLeaks was video of a 2007 Apache helicopter attack by American forces in Baghdad that killed 11 people, including two Reuters journalists.

“Julian has been indicted for receiving, possessing and communicating information to the public of evidence of war crimes committed by the U.S. government,” his wife, Stella Assange, said. “Reporting a crime is never a crime.”

U.S. lawyers say Assange is guilty of trying to hack the Pentagon computer and that WikiLeaks’ publications created a “grave and imminent risk” to U.S. intelligence sources in Afghanistan and Iraq.

While the U.S. criminal case against Assange was only unsealed in 2019, his freedom has been restricted for a dozen years.

Assange took refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London in 2012 and was granted political asylum after courts in England ruled he should be extradited to Sweden as part of a rape investigation in the Scandinavian country.

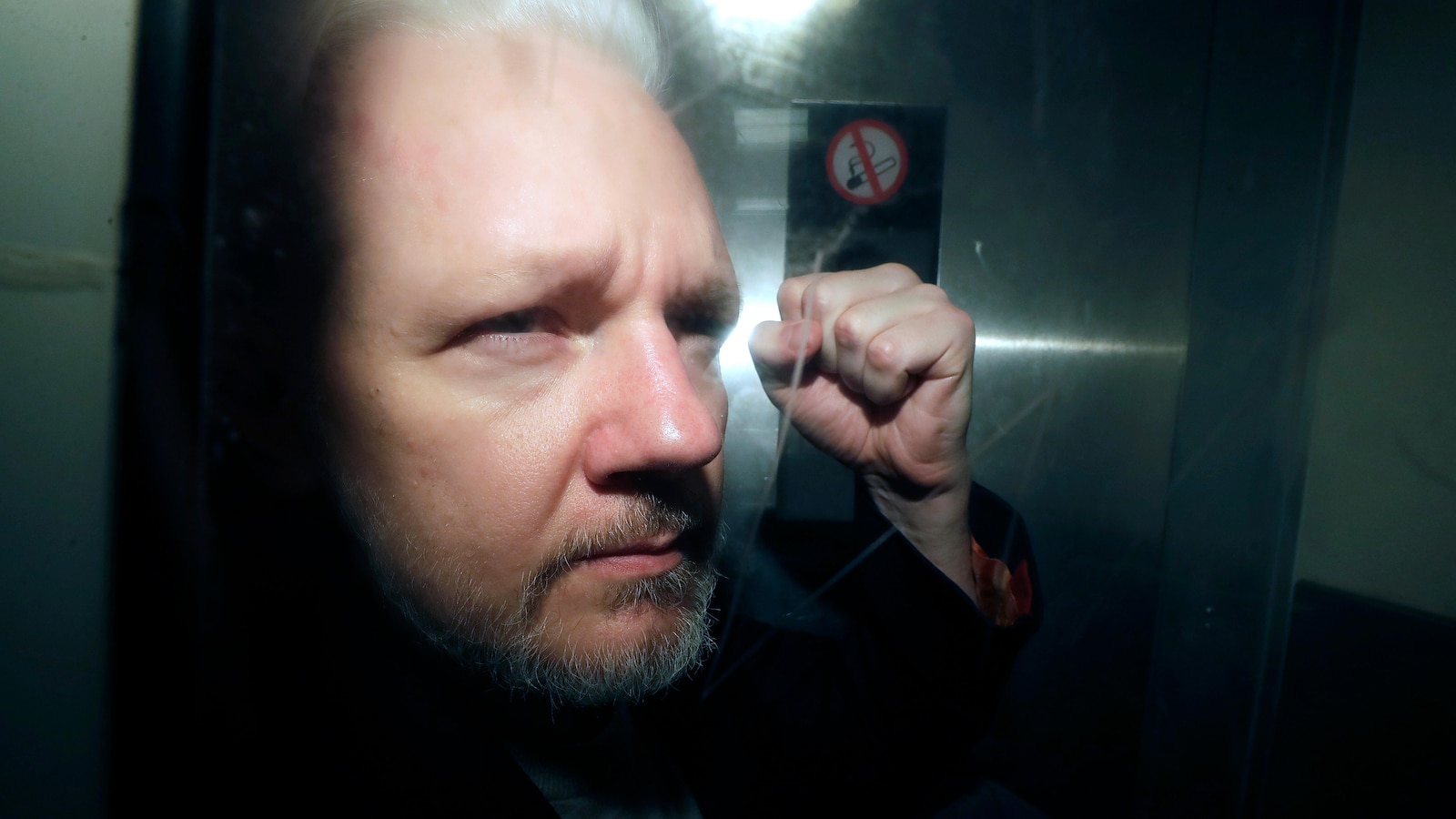

He was arrested by British police after Ecuador’s government withdrew his asylum status in 2019 and then jailed for skipping bail when he first took shelter inside the embassy.

Although Sweden eventually dropped its sex crimes investigation because so much time had elapsed, Assange has remained in London’s high-security Belmarsh Prison while the extradition battle with the U.S. continues.

His wife said his mental and physical health have deteriorated behind bars.

“He’s fighting to survive and that’s a daily battle,” she said.

A judge in London initially blocked Assange’s transfer to the U.S. in 2021 on the grounds he was likely to kill himself if held in harsh American prison conditions.

But subsequent courts cleared the way for the move after U.S. authorities provided assurances he wouldn’t experience the severe treatment that his lawyers said would put his physical and mental health at risk.

The British government authorized Assange’s extradition in 2022.

Assange’s lawyers raised nine grounds for appeal at a hearing in February, including the allegation that his prosecution is political.

The court accepted three of his arguments, issuing a provisional ruling in March that said Assange could take his case to the Court of Appeal unless the U.S. guaranteed he would not face the death penalty if extradited and would have the same free speech protections as a U.S. citizen.

The U.S. provided those reassurances three weeks later, though his supporters are skeptical.

Stella Assange said the “so-called assurances” were made up of “weasel words.”

WikiLeaks Editor-in-Chief Kristinn Hrafnsson said the judges had asked if Assange could rely on First Amendment protections.

“It should be an easy yes or no question,” Hrafnsson said. “The answer was, ‘He can seek to rely on First Amendment protections.’ That is a ‘no.’ So the only rational decision on Monday is for the judges to come out and say, ‘This is not good enough.’ Anything else is a judicial scandal.”

If Assange prevails, it would set the stage for an appeal process likely to further drag out the case.

If an appeal is rejected, his legal team plans to ask the European Court of Human Rights to intervene. But his supporters fear Assange could possibly be transferred before the court in Strasbourg, France, could halt his removal.

“Julian is just one decision away from being extradited,” his wife said.

Assange, who hopes to be in court Monday, has been encouraged by the work others have done in the political fight to free him, his wife said.

If he loses in court, he still may have another shot at freedom.

President Joe Biden said last month that he was considering a request from Australia to drop the case and let Assange return to his home country.

Officials have no other details but Stella Assange said it was “a good sign” and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the comment was encouraging.